This episode of Ballot and Beyond, contributed by the Maryland Women’s Heritage Center, was written by Audrey Partington. The reader is Kalin Thomas.

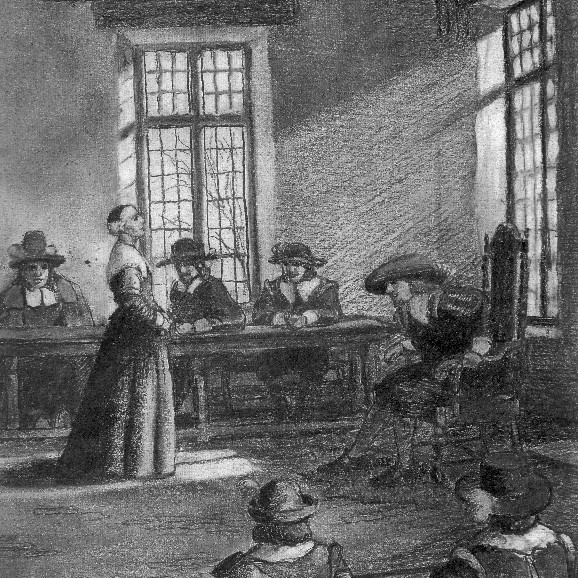

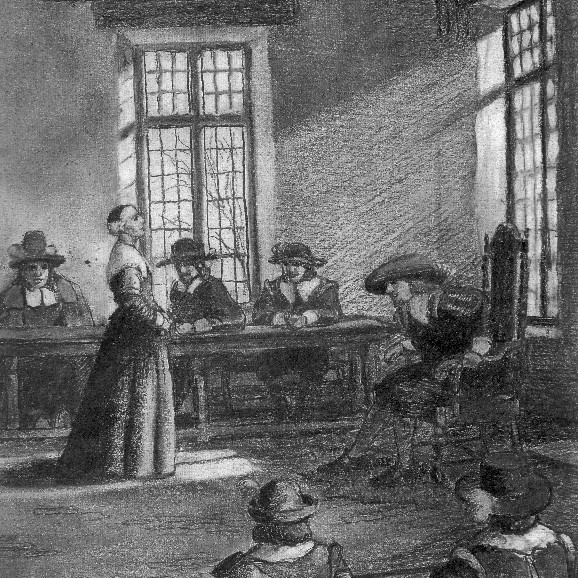

Two hundred years before the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, Margaret Brent became the first woman in the American colonies to request the right to vote.

Ballot & Beyond is powered by Preservation Maryland and PreserveCast with support from Gallagher Evelius & Jones and the Maryland Historical Trust.

Watch the full video episode on Margaret Brent here:

Two hundred years before the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, Margaret Brent became the first woman in the American colonies to request the right to vote.

Margaret was born into a wealthy English Catholic family, with close ties to Cecil Calvert (Lord Baltimore), the first Proprietor of the Maryland colony. He established the colony in 1634 as a safe haven for English Catholics fleeing persecution in Anglican England. Four years later, Margaret, along with a sister and two brothers, emigrated to Maryland carrying land grant orders from Lord Baltimore. They were to be granted the same amount of land given to the pioneer settlers. Brent established an estate near Saint Mary’s City, where she proceeded to trade in tobacco, indentured servants, and land.

Brent accumulated significant wealth and became a prominent citizen, earning the trust of Maryland’s colonial governor, Leonard Calvert, the brother of Lord Baltimore. Ten years after her arrival, Brent was one of the largest landowners in the New World.

At a time when married women were unable to own land, Margaret Brent remained single and in total control of her extensive property. She appeared frequently in colonial court to represent her own interests and those of her family and acquaintances. The American Bar Association recognizes Brent as the first woman lawyer in America. Records show that she successfully argued 124 cases over eight years.

Repercussions from the English civil war were felt in Maryland. In 1645, a Protestant sea captain, Richard Ingle, led a surprise attack on St. Mary’s City in the name of the English Parliament, which was at odds with Charles I. Governor Calvert fled to Virginia, and most of the Maryland Protestants left to become the first settlers in Virginia’s Northern Neck, just across the Potomac River from St. Mary’s.

Governor Calvert returned a year later with hired soldiers who defeated Ingle and his men. But the Governor soon became ill and died. On his deathbed, he named Margaret Brent as his executor, in charge of paying his debts and disposing of his estate. He instructed her to “take all and pay all.” Unfortunately, the Governor’s estate was not enough to repay the soldiers, who were threatening mutiny.

To deal with the crisis, Brent appeared before the Maryland Assembly on January 3, 1648, and asked to be named Lord Baltimore’s attorney, in place of the deceased Governor. The request was granted.

Several weeks later, Brent appealed to the Assembly to be granted two votes – one as landowner, and another as Lord Baltimore’s legal representative. The request was denied. Brent protested vehemently against the Assembly proceeding without her “vote and voyce.”

Brent had hoped to use her votes to convince the Assembly to levy a tax to pay the soldiers. With this avenue closed, she used her authority as Lord Baltimore’s attorney to sell his cattle to pay the soldiers.

Her actions avoided the rebellion of Calvert’s army and saved the Maryland colony as a haven for religious freedom. But Lord Baltimore was outraged, and condemned Brent’s actions in a letter to the Assembly. The Assembly defended Brent in a response to Lord Baltimore.

“We do Verily Believe and in Conscience report that it was better for the Colonies safety at that time in her hands than in any man’s else in the whole Province … for the Soldiers would never have treated any other with that Civility and respect, and though they were even ready at several times to run into mutiny yet she still pacified them … She rather deserved favour and thanks from your Honour … then those bitter invectives you have been pleased to Express against her.”

Lord Baltimore remained firm in his disapproval of Brent, leading her to sell some of her Maryland holdings and move to Virginia in 1651. At the time of her death in 1671, she had acquired nearly 10,000 acres of land.

Margaret Brent did not seek the right to vote for all women. She wanted to vote in the Maryland Assembly to save the colony. But future generations of suffragists were encouraged by her example of a strong, independent businesswoman, who advocated for herself and others in a court of law. Thanks to Brent, Marylanders can trace their state’s activism for woman suffrage all the way back to colonial America.

Previous episode