This episode of Ballot and Beyond, contributed by the Maryland Women’s Heritage Center, was written by Diane E. Weaver. The reader is Dr. Diane Weaver.

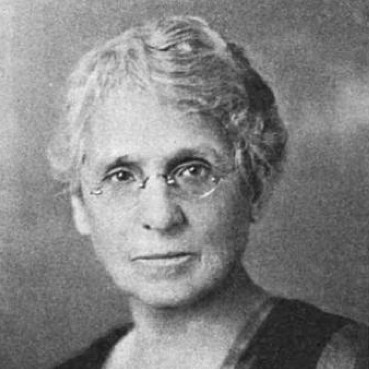

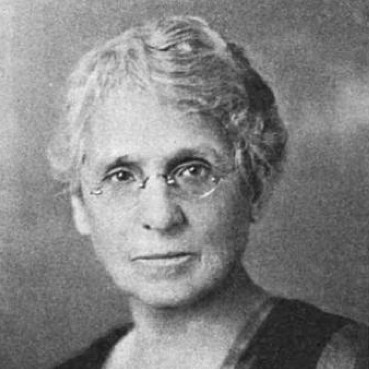

Madeleine Ellicott’s lifelong goal was to improve the lives of women and children and to secure equal rights for all human beings. She fought alongside thousands of women in pursuit of women’s right to vote. She firmly believed that only equal suffrage could right the wrongs against women. After the successful passage of the 19th Amendment, Ellicott’s compassion and activism for women’s political equality continued to shine bright and make change. She was the founder and twenty-year president of the Maryland League of Women Voters.

Ballot & Beyond is powered by Preservation Maryland and PreserveCast with support from Gallagher Evelius & Jones and the Maryland Historical Trust.

Madeleine Ellicott’s lifelong goal was to improve the lives of women and children and to secure equal rights for all human beings. She fought alongside thousands of women in pursuit of women’s right to vote. She firmly believed that only equal suffrage could right the wrongs against women.

Although Madeleine Ellicott as a young woman had nurtured a desire to pursue medical studies, with her father’s consent she studied chemistry at Rush Medical School and spent a year at the polytechnic in Zurich, Switzerland. Her marriage to Charles Ellis Ellicott, a descendant of the founder of Ellicott City, Maryland made her a relative by marriage to the late Elizabeth King Ellicott.

As Maryland’s suffrage movement matured, it used its network, as did other progressive activists, to rally support. Women throughout the state, in addition to working for a state constitutional amendment, gathered petitions for a federal amendment.

Madeleine Ellicott was an important leader in Maryland’s campaign for women’s suffrage. Writing in 1917 to suffrage activist Irma Graham in Salisbury, Wicomico County, Ellicott, vice president of the State Franchise League, referred to an “urgent” letter from Carrie Chapman Catt of NAWSA (National American Woman Suffrage Association).

Catt had requested information on Maryland’s petition drive, and Ellicott responded: “It will be mortifying if Maryland fails to do her duty towards this final drive…It is of course extremely difficult, but we should try and do our best.”

In 1918, with World War I over, national and Maryland suffrage activists returned to the issue they had for the most part placed in abeyance. The Congressional passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in June 1919 created one final legislative opportunity for Maryland suffragists. Suffrage leaders expected the ratification effort to be extremely difficult.

The growing conviction of the inevitability of national ratification was especially apparent among leaders of the Maryland Women’s Suffrage League. That conviction helped to explain a half-hearted ratification effort.

Madeleine Ellicott wrote to Roselle Handy in Worcester County, “I fear you will all have the vote thrust upon you before long, and then it will be citizenship schools before there is time for suffrage meetings.”

Ellicott was convinced that ratification was a dead issue in Maryland. “I think,” she wrote to Lilla Crawford in Hagerstown, “we should put very little energy and money in trying to influence the legislature for ratification. They will ratify when the bosses…tell them to do so… “ In March 1920, citing state’s rights, Maryland’s legislature defeated ratification. Tennessee became the thirty-sixth and deciding state to approve the Nineteenth Amendment.

After winning the right to vote, Madeleine Ellicott continued to advocate an “organized body” that would be free of partisan ties. At its Victory Convention in February 1920, NAWSA reconstituted itself as the National League of Women Voters.

As founder and twenty-year president of the Maryland League of Women Voters, in Ellicott’s view women should join political parties as well as work for their improvement as members of the League. Her enduring vision for the League encompassed bringing together women civic and party activists to pursue goals set by women, not for them.

Madeleine Ellicott died in 1945. She was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame in 1996.

Maryland’s General Assembly eventually did ratify the 19th Amendment—on March 29, 1941.

Previous episode