Historian and professor Jean Baker played a particularly important role in making a place for women in the public eye of history. She rightly observed that women are too often excluded from historical and academic accounts. Jean’s work in the larger women’s movement helped many see that the crux of history doesn’t have to be primarily male political leaders like kings, presidents, and prime ministers; that a traditional women’s role is also incredibly important to the understanding of past and current societies.

One hundred years ago, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States was signed into law and officially granted twenty million American women the right to vote.

This mass expansion in voting rights was the result of generations of intense activism known as the women’s suffrage movement that has had a lasting legacy on equality in America.

In recognition of the struggles and achievements of a once disenfranchised majority, PreserveCast is honored to share remarkable stories of suffragists within each episode this year.

Beyond the Ballot is supported by Preservation Maryland, Gallagher Evelius Jones law firm and the Maryland Historical Trust.

To learn more or to donate to support these efforts, please visit: ballotandbeyond.org.

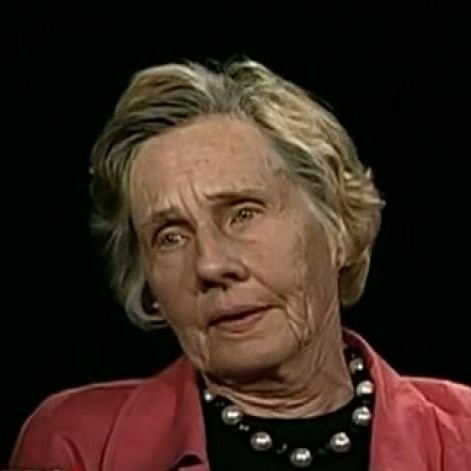

This week on Ballot and Beyond, we’ll learn about Jean Baker, a thoughtful historian who reexamined the place of women’s experiences in American history, read by Meagan Baco, Director of Communications at Preservation Maryland.

Jean Baker

Historian and Goucher College professor Jean Baker played a particularly important role in making a place for women in the public eye of history. She rightly observed that women are too often excluded from historical and academic accounts. Jean’s work in the larger women’s movement helped many see that the crux of history doesn’t have to be primarily male political leaders like kings, presidents, and prime ministers; that a traditional women’s role is also incredibly important to the understanding of past and current societies.

During her research, Jean Baker turned her attention to many suffragists including Lucy Diggs Slowe, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul and their campaign to secure the right to vote. She wrote the stories of their courage and persistence in the face of years of verbal and physical attacks. The New York Times cited Baker’s work as wider in scope than any previous work in making good use of sophisticated feminist, historical, and sociological scholarship.

In addition to profiles of suffragists, Professor Baker was particularly central in putting forth a more empathetic image of Mary Todd Lincoln. Mary Todd Lincoln, of course, was Abraham Lincoln’s wife and mother of his children including William Wallace Lincoln. He died from typhoid fever as a young boy. The loss was an emotional blow to both Mary and President Lincoln. But Jean Baker observed that Mary Todd Lincoln had been victimized by the press at the time and, consequently, by male historians for her emotions. Presumably, her reputation was in need of repair because she had stepped out of the expected quiet and almost invisible role of women in public.

“In her grief,” said Baker, “she cried too long and too hard. She disobeyed every rule of anonymity expected of ladies, especially of first ladies.” Baker said, “I responded to her mistreatment and to her sense of rivalry with everyone.” Baker’s work vividly recounted Mary Todd Lincoln’s sense of abandonment and desperation at the death of her child and, later, her paralyzing grief and fear at the death of her husband. The holistic and emotional lens of Jean Baker’s approach as a historian brought a depth of human emotion to her research and her writings that ultimately increased the understanding of Mary Todd, suffragists, and other women in history.

Fellow Goucher College professor, Laurie Kaplan, wrote to the Baltimore Sun that Jean Baker tells stories so convincingly and so authentically that the reader could feel the texture of the people and the families in her research as well as the weight and restrictions of those stresses felt by women in history. This accurate telling of women’s history is Jean Baker’s triumph.

Episode Gallery

Previous episode