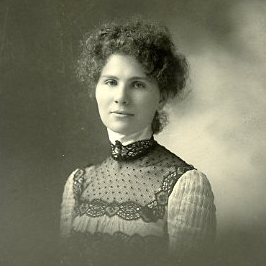

This episode of Ballot & Beyond, contributed by the Maryland Women’s Heritage Center, is adapted from a biographical sketch of Sadie Jacobs Crockin written by scholar Barry Kessler. The reader is Sally T. Grant, granddaughter of Sadie Crockin.

A wonderful summary of her life from the Jewish Museum of Maryland: As a woman, an American, and a Jew, Sadie Jacobs Crockin championed many causes. Throughout her life, she brought women together in organizations that empowered diverse Americans to participate fully in civic life. Crockin exemplified the college-educated, progressive “New Woman” of her day who joined women’s club for self-improvement and to effect social change. Under her leadership, the Baltimore chapter of the League of Women Voters helped women exercise their newly won right to vote. She was the founding president of the Baltimore chapter of Hadassah, the first Zionist women’s organization. Once she had firmly established these and other organizations locally, Crockin achieved statewide prominence as an advocate for social justice and women’s rights.

Ballot & Beyond is powered by Preservation Maryland, the state’s largest and oldest non-profit dedicated to Maryland’s public history, built heritage, and cultural landscapes.

Watch the video episode on Sadie Jacobs Crockin and her work in the Women’s Suffrage Movement here:

Sadie Jacobs Crockin was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1879, the eldest of 10 children. Her

family moved to Lynchburg, Virginia, where she graduated public high school, then attended

Randolph Macon Women’s College. Crockin graduated first in her class, winning the Oratory

Medal. This talent would do well for her as she entered a career in civic engagement.

When she married Emil Crockin, she returned to Baltimore, where her daughter,

Fried was born in 1905. Like most college-educated women of her day, Crockin joined

clubs that pursued social, educational, religious, civic and philanthropic interests. But

her passion was the “women’s suffrage” movement.

By 1911, Crockin was deeply engaged in the Maryland Equal Suffrage League. Working with

Madeleine Ellicott, president of the League, they set their sights on gaining the ballot box for all

women. Educating women was her mission, and soon she became Secretary and Chair of

Education for the League.

That same year, Crockin was elected recording secretary of the National Council of Jewish

Women’s Baltimore Section, and chaired the Immigrant Aid Committee. Later she organizes

and becomes the first president of Hadassah’s Baltimore chapter, a position she held for 13

years.

And yet, Crockin added even more to her list of activist duties, as she chaired the

Americanization Committees for the Equal Suffrage League, and volunteered with the

Maryland Council on Defense’s Female Section — a home front support agency during

World War I.

Two years later, Crockin became team captain for the American Red Cross Christmas

Seal campaign against tuberculosis. At that time Baltimore had the highest rate of infection

of any major American city. Later, her community called upon her to become a founder and

incorporator of the Baltimore Hebrew College.

The 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified in 1920, giving women the right to vote.

Carrie Chapman Catt and Maud Wood Park launched the League of Women Voters, a

nonpartisan issues oriented organization. Inspired by a thrilling speech by Park, the

League’s first president, Crockin stepped forward to lead the Baltimore chapter. At the

same time her dear friend and colleague, Madeleine Ellicott volunteered to lead Maryland’s

statewide group.

Crockin was at the helm of the Baltimore City League for 19 years. She threw herself into

organizing programs on citizenship, domestic policy and foreign affairs. She also played host

to the League of Women Voters Pan-American Conference in Baltimore. Attending

delegates include the most prominent women of Central and South America.

She guided the local league advocacy efforts to allow women to serve on juries,

to eliminate illiteracy in the city, and to establish a statewide system of juvenile

courts. She accepted appointments to several boards and commissions,

including: the Board of City Charities overseeing the City Hospital, the advisory

committee of the city’s Charter Revision Commission, and the State Commission

on Roadside Control and Beautification. Ever the activist, Crockin also became a

member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, the Women’s

Civic League and the Women’s City Club.

American-Born Sadie Jacobs Crockin, whose father and husband were both Jewish

immigrants, moved easily between different societies and people of all backgrounds. As

Jews entered the mainstream, she was able to bring multicultural groups together for mutual

benefit, before her death in 1965.

Her life inspired several of her descendants in promoting social justice. Her

granddaughter. Chaired the Maryland Commission for Women and is a past president of

the American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland. Her great, great granddaughter, Julia

Baez, is executive director of Baltimore’s Promise, and her great, great, great

Previous episode