This episode of Ballot and Beyond, contributed by the Maryland Women’s Heritage Center, is written and read by Christine R. Valeriann, a long-time board member of the Baltimore chapter of the National Organization for Women and a volunteer with the Maryland Women’s Heritage Center.

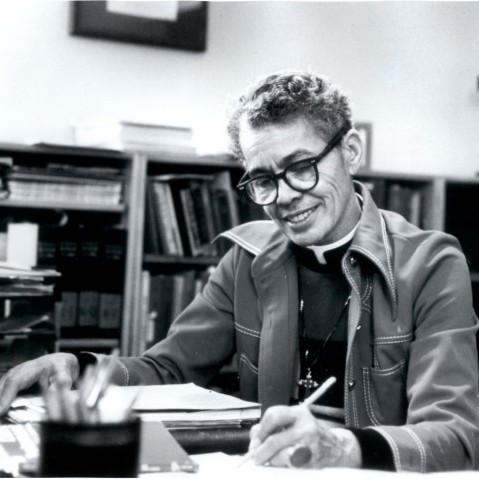

The Reverend Doctor Pauli Murray was ahead of her time and a pioneer in the areas of civil rights, feminism, labor, the law, academia, gender, and religion. Fifteen years before Rosa Parks, Murray was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a Virginia bus. Twenty years before Greensboro, she organized a sit-in to desegregate a restaurant. And 40 years before the language of intersectionality, she was invoking the race-sex analogy to describe black women’s positionality within the law.

Ballot & Beyond is powered by Preservation Maryland, the state’s largest and oldest non-profit dedicated to Maryland’s public history, built heritage, and cultural landscapes.

The Reverend Doctor Pauli Murray was ahead of her time and a pioneer in the areas of civil rights, feminism, labor, the law, academia, gender, and religion. Fifteen years before Rosa Parks, Murray was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a Virginia bus. Twenty years before Greensboro, she organized a sit-in to desegregate a restaurant. And 40 years before the language of intersectionality, she was invoking the race-sex analogy to describe black women’s positionality within the law.

One of the most important thinkers and legal scholars of the 20th century, she served as a bridge between the civil rights and women’s rights movements.

The granddaughter of a slave, and the great-granddaughter of a slave owner, Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray was born in Baltimore in 1910. At the age of three, after the death of her mother and medical incapacitation of her father, Murray was sent to North Carolina to live with a maternal aunt. Growing up in the “colored” section of Durham, she rebelled against the segregation that was an accepted fact of life, and refused to attend a segregated southern college.

She headed north. At the age of 16, she moved to New York City to attend Hunter College; she was both disheartened and motivated when she was rejected for admission. Determined to gain entry, she attended high school for a year in New York where she was the only Black among 4,000 students. She graduated from Hunter with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English in 1933.

After teaching for a few years, she headed back south, where she fought for admission to the all-white graduate school of the University of North Carolina–a school originally funded by her slave-owning ancestors. Murray’s fight received national publicity, and brought her to the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt, with whom she developed a life-long friendship. However, the campaign was unsuccessful and Murray was denied admission on the basis of race.

In 1940, Murray and a friend sat in the whites-only section of a Virginia bus. They politely refused when the bus driver asked them to move, and were arrested and jailed. This incident, and her subsequent involvement with the socialist Defense League, led Murray to pursue a career as a civil rights lawyer. Workers’

She enrolled in the law school at Howard University, where racism wasn’t an issue, but as the only female, sexism certainly was. She coined the term “Jane Crow” to name the forms of sexist derision she frequently encountered at the school. Murray and a group of female students employed one of the earliest uses of non-violent tactics. They successfully organized a sit-in demonstration, resulting in the desegregation of a cafeteria in Washington, D.C.

Murray graduated as the valedictorian of her class in 1944, and hoped to continue her law studies at Harvard University. She was awarded a prestigious fellowship and applied to Harvard, but was rejected because of her gender. Instead, she earned a master’s degree in law at the University of California, Berkeley; her master’s thesis was “The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment.”

In 1953, one of her former professors, Spottswood Robinson, pulled out a copy of her senior paper, and along with Thurgood Marshall and others, used it as a guide to strategize how they would argue the case of Brown v. Board of Education. As a lawyer, Murray argued for civil rights and women’s rights, and published her first book, “States’ Laws on Race and Color. Thurgood Marshall described her book as the “Bible” for civil rights lawyers.

In 1960 Murray travelled to Ghana to explore her cultural roots. When she returned, President Kennedy appointed her to his newly created Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. She criticized the way that men dominated leadership of civil rights organizations. She also served on the national board of the American Civil Liberties Union.

In 1965, she became the first African American to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree from Yale Law School. She began arguing that the Equal Protection Clause should be applied to cases of sex discrimination in much the same way that it had been applied to cases of racial discrimination. It was the piece co-authored by Murray in 1965 called “Jane Crow and the Law” that Ruth Bader Ginsburg cites as so influential in her thinking about legal remedies for sex discrimination. Ginsburg named Murray as a coauthor of a brief on the 1971 case of Reed v. Reed, in recognition that much of the legal groundwork for the argument could be attributed to Murray.

During a speech in New York, Murray suggested that women organize a march on Washington, which earned her a phone call from famous feminist, Betty Friedan. The next year in 1966, during a conference on women’s rights in Washington, D.C., a small group convened in Friedan’s hotel room. They discussed the failure of the EEOC to enforce Title VII of the Civil Rights Act–and founded the National Organization for Women. Murray was one of 28 women who contributed $5 each to help fund the formation of the organization, which she hoped would serve as an “NAACP for women’s rights.”

At the age of 68, Murray became the first Black woman, and one of the first women to be ordained in the Episcopal Church. In this capacity, she helped lay the groundwork for what we now know as womanist theology.

Murray was shaped by more than racism and sexism; she was a gender nonconforming person, who struggled both with her sexual and gender identity. In her younger years, she had occasionally passed as a teenage boy. She had asked doctors to administer male hormones to her, even trying to convince one doctor to perform exploratory surgery to see if she had “secreted male genitals.” She had a brief, annulled marriage to a man and several deep relationships with women.

Murray was never in the closet; but her career as an attorney, coupled with her Communist Party participation in early adulthood, made her an easy target. By the time she wrote her memoir, “Song in a Weary Throat,” published after she died in 1985, she had removed all explicit mention of her same-sex relationships.

Despite these wide-ranging and influential achievements, Murray’s name is not well known today, especially among white Americans. However, there has been a burst of interest in her legacy over the past few years: a residential college has been named after her at Yale, her childhood home has been designated a national historic landmark, and she has been sainted by the Episcopal Church.

Murray addressed her legacy in 1970 when she wrote: “If anyone should ask a Negro woman in America, what has been her greatest achievement, her honest answer would be, ‘I survived!’

The Reverend Doctor Pauli Murray did much more than survive.

Episode Gallery

Previous episode